Interview with Elizabeth Jane for the Historical Novel Society magazine

I read on your website that you started out wanting to tell the Rapunzel Story as a historical novel, as if it really happened (as part of your PhD?), until, as part of your research, came across Charlotte Rose de la Force who you describe as one of the 'most fascinating women ever forgotten by history,' and knew you had to write about her. Can you tell me about this process and at what point you decided the two stories must connect?

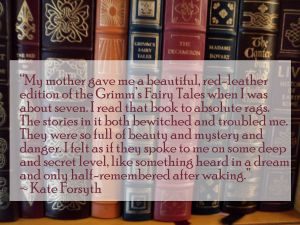

I began by wanting to rewrite ‘Rapunzel’. I’d been thinking about doing this since I was twelve, which is when I first tried to write a story based on the fairy tale. At that early age I knew I wanted to tell the story from the point of view of the girl locked in the tower. It was in my mid-teens when I realised I also wanted to tell part of the story from the point of view of the witch. So you can see it was a story I’d been interested in for a very long time.

I wrote many other books, but this idea still bothered me. One day I had an epiphany. I realised that I had been thinking of the book has a children’s fantasy, but that was why I had not been able to move forward with the idea. ‘Rapunzel’ was never meant as a children’s tale. It’s very dark and it’s very sexy. It’s a story of obsession, and madness, and desire, and resurrection, and it needed to be written for an adult audience. I also realised that I did not want to set it in a make-believe world. I wanted to set it in the real world, in our world, where girls are still kidnapped and locked up in attics all too often.

Once I realised I wanted to write the story as a historical novel for adults, I began thinking about the setting. Where and when would I set my Rapunzel retelling? I began to research the history of the tale, a decision that led me to undertaking my doctorate.

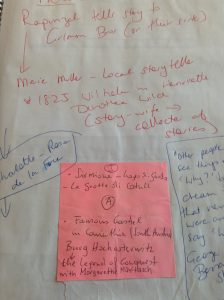

At the same time, I was playing with the idea of having a third narrative thread other than the stories of the maiden and the witch. I wanted the structure of the book to reflect the braid of impossibly long hair that is the most visually arresting motif of the story. I thought about the possibility of having one narrative thread set in contemporary times, with a girl locked away in a cellar, and I also thought about having the third narrative thread being someone – an old woman – telling the story to the Grimm brothers. I liked that idea, and so I began to research the background to the Grimm brothers’ fairy tales. It took me a long time, but eventually I discovered that the story I knew of as ‘Rapunzel’ was far older than the Grimms. I found the earliest known version had been written in the 1600s by Giambattista Basile, a man who was then working for the Venetian Republic. That set my imagination on fire, and so I began to envision the story set in late Renaissance Venice.

However, Basile’s story was not the story I knew. I wanted to retell the tale that had meant so much to me as a child. I had to track down how the story travelled from Venice to Germany, and how it changed along the way. Again it took me a long time, but eventually I discovered the story of Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de la Force, who wrote the version we know now of as ‘Rapunzel’. I knew at once I had to write about her – her life was full of drama and scandal and danger.

Regarding the viewpoint order in which you told the tale (brilliant, by the way), how did you determine what to reveal when? Did you know from the start that you would need the three viewpoints? Or did you write the three tales in full, chopping them up at a later point?

I knew I wanted three narrative viewpoints from the start, so I could weave them together like a braid. I wrote each strand separately, from the first word to the last word, as if I was writing three individual novels. I wrote Charlotte-Rose’s story first, with breaks to show where I would insert the other stories. Then I wrote Margherita’s story, from first word to last word, and wove it in to Charlotte-Rose’s story. Then I wrote my witch Selena’s story. My original plan had been to break it into sections and weave it through like the other two strands. However, I felt that would dissipate much of the power of her narrative, and so I changed my plan, and put Selena’s story, in its entirety, in the middle of the book. I call it the dark heart of the book.

You created such a plausible atmosphere of superstition and folk belief in 17th century France that the 'real magic' in the 16th century felt truly believable. How did you set out to achieve this?

Thank you so much! I always try and make the world of my story as vivid and alive as possible, so that you can really understand the forces working upon the characters. I read a great deal, including primary sources such as letters and memoirs, and I was particularly fascinated by the Affair of the Poisons – a scandal of murder and satanism which rocked the court of Louis XIV to its foundations.

When writing the sections set in Renaissance Venice, I read the work of an Italian historian, Carlo Ginzberg, who examined the Inquisition’s transcripts of 16th century witch trials. So many of the spells or practices in the book are ones which were actually recorded in Italy in the Renaissance.

How important is it to keep this element of the mysterious in fairy tale retellings?

It’s important for me! I think every creative artist brings their own passions and preoccupations to the task, and that is what makes their work so unique. I have always been fascinated by folklore and superstitions and the uncanny, and so my work reflects this interest.

How important do you think setting the story in a real time and place (as opposed to once-upon-a-time) were to achieving this?

For me, it was really important. I love the fantasy genre and many of my books are set far, far away, in make-believe lands. One of the great strengths of the fantasy genre is its quality of strangeness, and I love creating that type of world. However, with BITTER GREENS, I very much wanted to make it feel real, as if it had actually happened. I wanted to remind readers that the imprisonment of women against their wills is very much a cultural practice of our society … and it still happens. I did not want the escape hatch of magic, the sense that someone waved a wand and the impossible just happened. I wanted to find other reasons for the mysteries in the story.

Were the links to Titian art part of this decision? Or a happy coincidence?

Both!

I was working on Selena’s sections of the book and wanted to bring the world of Renaissance Venice vividly to life. I knew that I wanted her to be a courtesan, and that she had lived a remarkably long life without visible signs of ageing. I also knew, in the back of my mind, that I wanted to weave in something about Venetian art.

Then, one day, my son was doing a project on William Blake and I told him I had a book in my library that may be of help to him. I went and pulled the book on Blake out, and the book next to it fell out of the shelf and on to the floor. It was a book on Titian, and it had opened to a page showing colour plates of Titian’s paintings ‘Sacred & Profane Love’ and ‘Flora’, with a caption explaining how he used the same ideal of beauty in many of his paintings. Flicking though the book, I saw the same face appear again and again, and I remembered reading that Titian was thought to have been inspired by his mistress who had been a courtesan. I was absolutely electrified. I went racing to my study and started googling. Hours later, my son plaintively asked me if I had found the book on Blake … I had completely forgotten why I went into the library!

(Check out my Pinterest page on Titian to see all the paintings described in Bitter Greens)

Were the witches incantations a product of your imagination? Or did you find similar examples in historical sources? For example was bathing in the blood of virgins a real superstition that you utilised for your purposes? Or did you make it up? How important is it to the overall plausibility to find such connections?

I was inspired by Carlo Ginzberg’s work on 16th century Inquisition court transcripts, which contained a great deal of fascinating information on magical beliefs and superstitions of the time. I was also interested in other medieval accounts of witchcraft such as the Malleus Maleficarum. The idea of bathing in the blood of a virgin to preserve beauty is not new. It was a common belief of the time. The Hungarian Countess Erzsébet Báthory was thought to have murdered hundreds of girls in the early 1600s for this purpose. I always like to have the magic in my stories deeply rooted in the real. It makes it feel more possible.

How important do you think a surprise ending is to a fairy tale re-telling? How important is it to have a hitherto unexplored perspective?

I think surprise is the magic ingredient of all good storytelling. I am always thinking to myself, how can I best surprise the reader? I think this is even more important in a fairy-tale retelling, because the story’s structure and motifs are so familiar to most readers. ‘Rapunzel’ is one of the best known tales in the world, and so the challenge for me was to transform it into a compelling, suspenseful and unexpected reading experience.

You worked with a translator? Was this frustrating? Did you have a sense that if you could have just read the materials yourself you might have uncovered more? What did you tell the translator you were looking for?

My translator translated every single word for me, so there was no need for me to worry about missing things. It was a massive job. Sylvie translated some of Charlotte-Rose de la Force’s fairy tales that had never before been translated, plus a

brief autobiographical sketch she had written, as well as a biography of Charlotte-Rose written by a French academic. She also communicated for me with some French fairy tale experts, and with the Comte de Sabran-Pontevès, a descendant of the La Force family who still lives in the Chateau de Cazeneuve where Charlotte-Rose grew up. Then, when I went to France and visited the Chateau, I hired another translator to go with me to help me communicate with the Comte (he gave me a private tour of the chateau – it was absolutely amazing! I saw Charlotte-Rose’s pram and her baptismal records which proved her birth age).

What would you say were the main themes of your novel? If I were to take a guess I would say redemption - which, I believe, is an element of the de la Force version of the tale that appealed to you.

Yes, I think it is all about redemption. The ‘Rapunzel’ fairy tale has its roots in ancient nature myths. All the characters in it – maiden, prince, crone - journey through death and darkness into light and rebirth again. It’s extraordinarily beautiful and powerful.

Was this part of your decision to give the witch a viewpoint - indeed, to create an empathy for her in the reader's minds?

Yes, this was an important aspect of the tale for me.

Through her life, and that of Charlotte-Rose, did you also want to show the limited options for women apart from the church or marriage?

This was certainly important for me too. I always think that I am living the life Charlotte-Rose dreamed of. I was free to choose who to love, and free to write as I please. Its important women never forget how far we have come, and how hard the battle has been.

In Mirror Mirror (Bernheimer, Kate, Anchor Books, 2002), Margaret Atwood describes an antipathy for 'pinkly illustrated versions of Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty stories whose plots were dependant on female servility, immobility or even stupor, and on princely rescue.' I believe one of the reasons you liked de la Force's version of the Rapunzel tale is because the woman in the tower takes a more active role in her own redemption. Indeed, in Bitter Greens, Lucio tells her Margherita, that she must look in her heart and find a way to break the spell. Can you talk to me about your reasoning here? Is your novel a conscious attempt to fight against the helpless princess stereotype?

It always makes me cross when people call Rapunzel the ‘passive princess waiting patiently for her prince’. She is not a princess, she does not wait patiently but rather sings with all her heart and soul and so draws the prince to her, and she is the one that saves the prince, not the other way around. She is a mythic figure of feminine power, who frees herself and then heals the blinded eyes of the prince. It is true that she is held in stasis and immobility in the first part of the story, but never forget that she escapes her tower at the end. That is the whole point of the story.

As you know, the fairy tale was an oral storytelling tradition long before it ever became a literary form, with each teller altering the tale for their own purposes. Do you see your own re-telling of Rapunzel as contributing to this tradition? Would your twenty first century message be that women hold the key to their own destiny? How does Charlotte-Rose de la Force's life further illustrate this theme?

Yes, I like to think of myself as being the latest in a long chain of storytellers, both oral and literary, who have told and retold the tale from the very beginning of human history. I imagine the story as a flame, passed from hand to hand, casting light into the world.

And remember that it is not only women who are held captive by the metaphorical towers of society. Men are too. Fairy tales are a window into the human psyche, and hold wisdom for us all.

A little question aside from fairy tales ... In the chapter A Mere Bagatelle you have a delightful argument between Michel Baron and Charlotte-Rose about their writing. Some of the memorable lines are: 'All these disguises duels and abductions... All these desperate love affairs. And you wish me to take you seriously.' 'I like disguises and duels... At least something happens in my stories.' 'At least my plays are about something.' Etc... How does this describe your own working life? Where you sit on the literary spectrum? Like Charlotte-Rose do you see yourself as an intelligent female writer of fantasy/historical fiction who has a literary turn of phrase yet also wants to tell a good story, with themes like love and redemption, that women in particular will enjoy?

I’m glad you enjoyed that scene! I have let Charlotte-Rose speak for me there. I too like stories in which things happen, and I too think that stories about love express one of the most universal human longings. Like Charlotte-Rose, I relish language, for its beauty, and for its ability to help us articulate ideas and emotions, and connect with other humans. I love storytelling, and am not interested in books that fail to tell a good story. Yet I want to think as well as feel, and so I love books that are full of big ideas, where I learn new things, and come to understand something that has always eluded me before. I see no reason why a page-turning, compelling story cannot be well-written too!